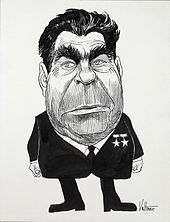

Leonid Brezhnev

- Birth Date:

- 19.12.1906

- Death date:

- 10.11.1982

- Length of life:

- 75

- Days since birth:

- 43094

- Years since birth:

- 117

- Days since death:

- 15374

- Years since death:

- 42

- Person's maiden name:

- Леонид Ильич Брежнев

- Extra names:

- Leonīds Brežņevs, Леонид Брежнев, Леонид Ильич Брежнев, Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev , Леоні́д Іллі́ч Бре́жнєв

- Categories:

- Communist, Communist Party worker, Hero of the Soviet Union, Member of the Government, Military person, Publicist, WWII participant

- Cemetery:

- Kremlin Wall Necropolis

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (Russian: Леони́д Ильи́ч Бре́жнев; IPA: [lʲɪɐˈnʲid ɪlʲˈjitɕ ˈbrʲeʐnʲɪf] (![]() listen); Ukrainian: Леоні́д Іллі́ч Бре́жнєв, 19 December 1906 (O.S. 6 December) – 10 November 1982) was the General Secretary of the Central Committee (CC) of theCommunist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), presiding over the country from 1964 until his death in 1982. His eighteen-year term as General Secretary was second only to that of Joseph Stalin in length. During Brezhnev's rule, the global influence of the Soviet Union grew dramatically, in part because of the expansion of the Soviet military during this time, but his tenure as leader has often been criticised for marking the beginning of a period of economic stagnation in which serious economic problems were overlooked, problems which eventually led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

listen); Ukrainian: Леоні́д Іллі́ч Бре́жнєв, 19 December 1906 (O.S. 6 December) – 10 November 1982) was the General Secretary of the Central Committee (CC) of theCommunist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), presiding over the country from 1964 until his death in 1982. His eighteen-year term as General Secretary was second only to that of Joseph Stalin in length. During Brezhnev's rule, the global influence of the Soviet Union grew dramatically, in part because of the expansion of the Soviet military during this time, but his tenure as leader has often been criticised for marking the beginning of a period of economic stagnation in which serious economic problems were overlooked, problems which eventually led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Brezhnev was born in Kamenskoe into a Russian worker's family. After graduating from the Dniprodzerzhynsk Metallurgical Technicum, he became a metallurgical engineer in the iron and steel industry, in Ukraine. He joined Komsomol in 1923, and in 1929 became an active member of the Communist Party. He was drafted into immediate military service during World War II and left the army in 1946 with the rank of Major General. In 1952 Brezhnev became a member of the Central Committee, and in 1964, Brezhnev succeeded Nikita Khrushchev as First Secretary. Alexei Kosygin succeeded Khrushchev in his post as Chairman of the Council of Ministers.

As a leader, Brezhnev took care to consult his colleagues before acting, but his attempt to govern without meaningful economic reforms led to a national decline by the mid-1970s, a period referred to as the Era of Stagnation. A significant increase in military expenditure, which by the time of Brezhnev's death stood at approximately 15% of the country's GNP, and an aging and ineffective leadership set the stage for a dwindling GNP compared to Western nations. While at the helm of the USSR, Brezhnev pushed for détente between the Eastern and Western countries. He presided over the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia to stop the Prague Spring, and his last major decision in power was to send the Soviet military to Afghanistan in an attempt to save the fragile regime which was fighting a war against the mujahideen.

Brezhnev died on 10 November 1982 and was quickly succeeded in his post as General Secretary by Yuri Andropov. Brezhnev had fostered a cult of personality, although not to the same degree as Stalin. Mikhail Gorbachev, who would lead the USSR from 1985 to 1991, denounced his legacy and drove the process of liberalisation of the Soviet Union.

Origins and education

Brezhnev was born on 19 December 1906 in Kamenskoe (now Dniprodzerzhynsk in Ukraine), to metalworker Ilya Yakovlevich Brezhnev and his wife, Natalia Denisovna. At different times during his life, Brezhnev specified his ethnic origin alternately as either Ukrainian or Russian, opting for the latter as he rose within the Communist Party. Like many youths in the years after the Russian Revolution of 1917, he received a technical education, at first in land management where he started as a land surveyor and then in metallurgy. He graduated from the Dniprodzerzhynsk Metallurgical Technicum in 1935 and became a metallurgical engineer in the iron and steel industries of eastern Ukraine.

Political development

Brezhnev joined the Communist Party youth organisation, the Komsomol, in 1923, and the Party itself in 1929. In 1935 and 1936, Brezhnev served his compulsory military service, and after taking courses at a tank school, he served as a political commissar in a tank factory. Later in 1936, he became director of the Dniprodzerzhynsk Metallurgical Technicum (technical college). In 1936, he was transferred to the regional center of Dnipropetrovsk and, in 1939, he became Party Secretary in Dnipropetrovsk, in charge of the city's important defence industries. As a survivor of Stalin's Great Purge of 1937–39, he could gain rapid promotions, since the purges opened up many positions in the senior and middle ranks of the Party and state.

Second World War

When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Brezhnev was, like most middle-ranking Party officials, immediately drafted. He worked to evacuate Dnipropetrovsk's industries to the east of the Soviet Union before the city fell to the Germans on 26 August, and then was assigned as a political commissar. In October, Brezhnev was made deputy of political administration for theSouthern Front, with the rank of Brigade-Commissar.

When Ukraine was occupied by the Germans in 1942, Brezhnev was sent to the Caucasus as deputy head of political administration of the Transcaucasian Front. In April 1943, he became head of the Political Department of the 18th Army. Later that year, the 18th Army became part of the 1st Ukrainian Front, as the Red Army regained the initiative and advanced westwards through Ukraine. The Front's senior political commissar was Nikita Khrushchev, who became an important patron of Brezhnev's career. Brezhnev had met Khrushchev in 1931, shortly after joining the party, and before long, as he continued his rise through the ranks, he became Khrushchev's protégé. At the end of the war in Europe, Brezhnev was chief political commissar of the 4th Ukrainian Front which entered Prague after the German surrender.

Immediate post war

Brezhnev left the Soviet Army with the rank of Major General in August 1946. He had spent the entire war as a commissar rather than a military commander. After working on reconstruction projects in Ukraine, he again became First Secretary in Dnipropetrovsk. In 1950, he became a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, the Soviet Union's highest legislative body. Later that year he was appointed Party First Secretary in Moldavia. In 1952, he became a member of the Communist Party's Central Committee and was introduced as a candidate member into the Presidium (formerly the Politburo).

Stalin died in March 1953, and in the reorganisation that followed, the Presidium was abolished and a smaller Politburo reconstituted. Although Brezhnev was not made a Politburo member, he was appointed head of the Political Directorate of the Army and the Navy with the rank of Lieutenant-General, a very senior position. This was probably due to the new power of his patron Khrushchev, who had succeeded Stalin as Party General Secretary. On 7 May 1955, Brezhnev was made Party First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Kazakh SSR. His brief was simple: to make the new lands agriculturally productive. With this directive, he started the initially successful Virgin Lands Campaign. Brezhnev was recalled to Moscow in 1956. The harvest in the following years of the Virgin Lands Campaign was disappointing, which would have hurt his political career if he had stayed.

In February 1956, Brezhnev returned to Moscow, promoted to candidate member of the Politburo and assigned control of the defence industry, the space program, heavy industry, and capital construction. He was now a senior member of Khrushchev's entourage, and in June 1957, he backed Khrushchev in his struggle with the Stalinist old guard in the Party leadership, the so-called "Anti-Party Group". Following the defeat of the old guard, Brezhnev became a full member of the Politburo. Brezhnev became Second Secretary of the Central Committee in 1959, and in May 1960 was promoted to the post of Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, making him the nominal head of state, although the real power resided with Khrushchev as First Secretary. In 1962, Brezhnev became an honorary citizen of Belgrade.

Removal of Khrushchev

Until about 1962, Khrushchev's position as Party leader was secure; but as the leader aged, he grew more erratic and his performance undermined the confidence of his fellow leaders. The Soviet Union's mounting economic problems also increased the pressure on Khrushchev's leadership. Outwardly, Brezhnev remained loyal to Khrushchev, but he became involved in a 1963 plot to remove the leader from power, possibly playing a leading role. In 1963 also, Brezhnev succeeded Frol Kozlov, another Khrushchev protégé, as Secretary of the Central Committee, positioning him as Khrushchev's likely successor. Khrushchev made him Second Secretary, literally deputy party leader, in 1964.

After returning from Scandinavia and Czechoslovakia in October 1964, Khrushchev, unaware of the plot, went on holiday in Pitsunda, near the Black Sea. Upon his return, his Presidium officers congratulated him for his work in office. Anastas Mikoyan visited Khrushchev, hinting that he should not be too complacent about his present situation. Vladimir Semichastny, head of the KGB, was a crucial part of the conspiracy, as it was his duty to inform Khrushchev if anyone was plotting against his leadership. Nikolay Ignatov, who had been sacked by Khrushchev, discreetly requested the opinion of several Central Committee members. After some false starts, fellow conspirator Mikhail Suslov phoned Khrushchev on 12 October and requested that he return to Moscow to discuss the state of Soviet agriculture. Finally Khrushchev understood what was happening, and said to Mikoyan, "If it's me who is the question, I will not make a fight of it".[15] While a minority headed by Mikoyan wanted to remove Khrushchev from the office of First Secretary but retain him as the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, the majority, headed by Brezhnev, wanted to remove him from active politics altogether.

Brezhnev and Nikolai Podgorny appealed to the Central Committee, blaming Khrushchev for economic failures, and accusing him of voluntarism and immodest behavior. Influenced by the Brezhnev allies, Politburo members voted to remove Khrushchev from office. In addition, some members of the Central Committee wanted him to undergo punishment of some kind. But Brezhnev, who had already been assured the office of the General Secretary, saw little reason to punish his old mentor further. Brezhnev was appointed First Secretary, but at the time was believed to be a transition leader of sorts, who would only "keep the shop" until another leader was appointed. Alexei Kosygin was appointed head of government, and Mikoyan was retained as head of state. Brezhnev and his companions supported the general party line taken afterJoseph Stalin's death, but felt that Khrushchev's reforms had removed much of the Soviet Union's stability. One reason for Khrushchev's ousting was that he continuously overruled other party members, and was, according to the plotters, in contempt of the party's collective ideals. Pravda, a newspaper in the Soviet Union, wrote of new enduring themes such as collective leadership, scientific planning, consultation with experts, organisational regularity and the ending of schemes. When Khrushchev left the public spotlight, there was no popular commotion, as most Soviet citizens, including the intelligentsia, anticipated a period of stabilisation, steady development of Soviet society and continuing economic growth in the years ahead.

Consolidation of power

Early policy reforms were seen as predictable. In 1964, a plenum of the Central Committee forbade any single individual to hold the two most powerful posts of the country (the office of the General Secretary and the Premier). Former Chairman of the State Committee for State Security (KGB) Alexander Shelepin disliked the new collective leadership and its reforms. He made a bid for the supreme leadership in 1965 by calling for restoration of "obedience and order". Shelepin failed to gather support in the Presidium and Brezhnev's position was fairly secure; however, he was not able to remove Shelepin from office until 1967.

Khrushchev was removed mainly because of his disregard of many high-ranking organisations within the CPSU and the Soviet government. Throughout the Brezhnev era, the Soviet Union was controlled by a collective leadership (officially coined "Collectivity of leadership") at least through the late 1960s and 1970s. The consensus within the party was that the collective leadership prevailed over the supreme leadership of one individual. T.H. Rigby argued that by the end of the 1960s, a stable oligarchic system had emerged in the Soviet Union, with most power vested around Brezhnev, Kosygin and Podgorny. While the assessment was true at the time, it coincided with Brezhnev's strengthening of power by means of an apparent clash with Central Committee Secretariat Mikhail Suslov. American Henry A. Kissinger, in the 1960s, mistakenly believed Kosygin to be the dominant leader of Soviet foreign policy in the Politburo. During this period, Brezhnev was gathering enough support to strengthen his position within Soviet politics. In the meantime, Kosygin was in charge of economic administration in his role as Chairman of the Council of Ministers. However, Kosygin's position was weakened when he proposed an economic reform in 1965, which was widely referred to as the "Kosygin reform" within the Communist Party. The reform led to a backlash, and party Conservatives continued to oppose Kosygin after witnessing the results of reforms leading up to the Prague Spring. His opponents then flocked to Brezhnev, and they helped him in his task of strengthening his position within the Soviet system.[22]

Brezhnev was adept at the politics within the Soviet power structure. He was a team player and never acted rashly or hastily; unlike Khrushchev, he did not make decisions without substantial consultation with his colleagues, and was always willing to hear their opinions. During the early 1970s, Brezhnev consolidated his domestic position. In 1977, he forced the retirement of Podgorny and became once again Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, making this position equivalent to that of an executive president. While Kosygin remained Premier until shortly before his death in 1980 (replaced by Nikolai Tikhonov as Premier), Brezhnev was the dominant driving force of the Soviet Union from the mid-1970s to his death in 1982.

Repression

Brezhnev's stabilisation policy included ending the liberalising reforms of Khrushchev, and clamping down on cultural freedom. During the Khrushchev years, Brezhnev had supported the leader's denunciations of Stalin's arbitrary rule, the rehabilitation of many of the victims of Stalin's purges, and the cautious liberalisation of Soviet intellectual and cultural policy. But as soon as he became leader, Brezhnev began to reverse this process, and developed an increasingly conservative and regressive attitude.

The trial of the writers Yuli Daniel and Andrei Sinyavsky in 1966—the first such public trials since Stalin's day—marked the reversion to a repressive cultural policy. Under Yuri Andropovthe state security service (in the form of the KGB) regained some of the powers it had enjoyed under Stalin, although there was no return to the purges of the 1930s and 1940s, and Stalin's legacy remained largely discredited among the Soviet intelligentsia. On 22 January 1969, a Soviet Army deserter, Viktor Ilyin, tried to assassinate Brezhnev and was diagnosed as mentally ill and placed in solitary confinement in a psychiatric hospital. By the mid-1970s, there were an estimated 10,000 political and religious prisoners across the Soviet Union, living in grievous conditions and suffering from malnutrition. Many of these prisoners were considered by the Soviet state to be mentally unfit and were hospitalised in mental asylums across the Soviet Union. Under Brezhnev's rule, the KGB infiltrated most, if not all, anti-government organisations, which ensured that there was little to no opposition against him or his power base. Brezhnev did however refrain from the all-out violence seen under the rule of Stalin.

Society

Over the eighteen years that Brezhnev ruled the Soviet Union, average income per head increased by half; however, three-quarters of this growth came in the 1960s and early 1970s. During the second half of Brezhnev's reign, average income per head grew by one-quarter. In the first half of the Brezhnev period, income per head increased by 3.5% per annum; slightly less growth than what it had been the previous years. This can be explained by Brezhnev's reversal of most of Khrushchev's policies. Consumption per head rose by an estimated 70% under Brezhnev, but with three-quarters of this growth happening before 1973 and only one-quarter in the second half of his rule. Most of the increase in consumer production in the early Brezhnev era can be attributed to the Kosygin reform.

When the USSR's economic growth stalled in the 1970s, the standard of living and housing quality improved significantly. Instead of paying more attention to the economy, the Soviet leadership under Brezhnev tried to improve the living standard in the Soviet Union by extending social benefits. This led to an increase, though a minor one, in public support. The standard of living in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) had fallen behind that of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (GSSR) and the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic (ESSR) under Brezhnev; this led many Russians to believe that the policies of the Soviet Government were hurting the Russian population. The state usually moved workers from one job to another which ultimately became an ineradicable feature in Soviet industry. Government industries such as factories, mines and offices were staffed by undisciplined personnel who put a great effort into not doing their jobs; this ultimately led, according to Robert Service, to a "work-shy workforce". The Soviet Government had no effective counter-measure because of the country's lack of unemployment.

While some areas improved during the Brezhnev era, the majority of civilian services deteriorated and living conditions for Soviet citizens fell rapidly. Diseases were on the rise because of the decaying healthcare system. The living space remained rather small by First World standards, with the average Soviet person living on 13.4 square metres. Thousands ofMoscow inhabitants became homeless, most of them living in shacks, doorways and parked trams. Nutrition ceased to improve in the late 1970s, while rationing of staple food products returned to Sverdlovsk for instance. The state provided recreation facilities and annual holidays for hard-working citizens. Soviet trade unions rewarded hard-working members and their families with beach vacations in Crimea and Georgia.

Social rigidification became a common feature of Soviet society. During the Stalin era in the 1930s and 1940s, a common labourer could expect promotion to a white-collar job if he studied and obeyed Soviet authorities. In Brezhnev's Soviet Union this was not the case. Holders of attractive positions clung to them as long as possible; mere incompetence was not seen as a good reason to dismiss anyone. In this way, too, the Soviet society Brezhnev passed on had become static.

Soviet–US relations

During his eighteen years as Leader of the USSR, Brezhnev's only major foreign policy innovation was détente. However, this did not differ much from the Khrushchev Thaw, a domestic and foreign policy relaxation started by Nikita Khrushchev. Historian Robert Service sees détente simply as a continuation of Khrushchev's foreign policy. Despite some increased tension under Khrushchev, East–West relations had generally improved, as evidenced by the Partial Test Ban Treaty, the Helsinki Accords and the installation of the red telephone line between the White House and the Kremlin. But Brezhnev's détente policy differed from that of Khrushchev in two ways. The first was that it was more comprehensive and wide-ranging in its aims, and included signing agreements on arms control, crisis prevention, East–West trade, European security and human rights. The second part of the policy was based on the importance of equalising the military strength of the United States and the Soviet Union. Defence spending under Brezhnev between 1965 and 1970 increased by 40%, and annual increases continued thereafter. In the year of Brezhnev's death in 1982, fifteen percent of GNP was spent on the military.

By the mid-1970s, it had become clear that Kissinger's policy of détente towards the Soviet Union had failed. The détente had rested on the assumption that a "linkage" of some type could be found between the two countries, with the US hoping that the signing of SALT I and an increase in Soviet–US trade would stop the aggressive growth of communism in the third world. This did not happen, and the Soviet Union started funding thecommunist guerillas who fought actively against the US during the Vietnam War. The US lost the Vietnam War and at the same time lost Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam to communism. After Gerald Ford lost the presidential election to Jimmy Carter, American foreign policies became more hostile towards the Soviet Union and the communist world, though attempts were also made to stop funding for some repressive anti-communist governments the United States supported. While at first standing for a decrease in all defense initiatives, the later years of Carter's presidency would increase spending on the US military.

In the 1970s, the Soviet Union reached the peak of its political and strategic power in relation to the United States. The first SALT Treaty effectively established parity in nuclear weapons between the two superpowers, the Helsinki Treaty legitimised Soviet hegemony over Eastern Europe, and the United States defeat in Vietnam and the Watergate scandal weakened the prestige of the United States. Brezhnev and Nixon also agreed to pass the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, which banned both countries to design systems that would intercept incoming missiles so that neither the U.S. or the Soviet Union would be tempted to strike the other without the fear of retaliation. The Soviet Union extended its diplomatic and political influence in the Middle East and Africa.

[edit]The Vietnam WarNikita Khrushchev had initially supported North Vietnam out of "fraternal solidarity", but as the war escalated he had urged the North Vietnamese leadership to give up the quest of liberatingSouth Vietnam. He continued by rejecting an offer of assistance made by the North Vietnamese government, and instead told them to enter negotiations in the United Nations Security Council. After Khrushchev's ousting, Brezhnev resumed aiding the communist resistance in Vietnam. In February 1965, Kosygin travelled to Hanoi with a dozen Soviet air force generals and economic experts. During the Soviet visit, President Lyndon B. Johnson had authorised US bombing raids on North Vietnamese soil in retaliation for a recent attack by theViet Cong.

Johnson privately suggested to Brezhnev that he would guarantee an end to South Vietnamese hostility if Brezhnev would guarantee a North Vietnamese one. Brezhnev was interested in this offer initially, but after being told by Andrei Gromyko that the North Vietnamese government was not interested in a diplomatic solution to the war, Brezhnev rejected the offer. The Johnson administration responded to this rejection by expanding the American presence in Vietnam, but later invited the USSR to negotiate a treaty concerning arms control. The USSR simply did not respond, initially because Brezhnev and Kosygin were fighting over which of them had the right to represent the USSR abroad, but later because of the escalation of the "dirty war" in Vietnam. In early 1967, Johnson offered to make a deal with Ho Chi Minh, and said he was prepared to end US bombing raids in North Vietnam if Ho ended his infiltration of South Vietnam. The US bombing raids halted for a few days and Kosygin publicly announced his support for this offer. The North Vietnamese government failed to respond however, and because of this, the US continued its raids in North Vietnam. The Brezhnev leadership concluded from this event that seeking diplomatic solutions to the ongoing war in Vietnam was hopeless. Later in 1968, Johnson invited Kosygin to the United States to discuss ongoing problems in Vietnam and the arms race. The summit was marked by a friendly atmosphere, but there were no concrete breakthroughs by either side.

In the aftermath of the Sino–Soviet border conflict, the Chinese continued to aid the North Vietnamese regime, but with the death of Minh in 1969, China's strongest link to Vietnam was gone. In the meantime, Richard Nixon had been elected President of the United States. While having been known for his anti-communist rhetoric, Nixon said in 1971 that the US "must have relations with Communist China". His plan was for a slow withdrawal of US troops from Vietnam, while still retaining the capitalist dictatorship of South Vietnam. The only way he thought this was possible was by improving relations with both Communist China and the USSR. He later made a visit to Moscow to negotiate a treaty on arms control and the Vietnam war, but on Vietnam nothing could be agreed. On his visit to Moscow, Nixon and Brezhnev signed the SALT I, marking the beginning of the "détente" era, which would be proclaimed a "new era of peaceful coexistence" that would replace the hostility that existed during the Cold War.

Cult of personality

The last years of Brezhnev's rule were marked by a growing personality cult. His love of medals (he received over 100), was well known, so in December 1966, on his 60th birthday, he was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union. Brezhnev received the award, which came with the Order of Lenin and the Gold Star, three more times in celebration of his birthdays. On his 70th birthday he was awarded the Marshal of the Soviet Union – the highest military honour in the Soviet Union. After being awarded the medal, he attended an 18th Army Veterans meeting, dressed in a long coat and saying; "Attention, Marshal's coming!". He also conferred upon himself the rare Order of Victory in 1978 — the only time the decoration was ever awarded outside of World War II. (This medal was posthumously revoked in 1989 for not meeting the criteria for citation).

Brezhnev's weakness for undeserved medals was proven by his poorly written memoirs recalling his military service during World War II. Despite the apparent weaknesses of his memoirs, they were awarded the Lenin Prize for Literature and were met with critical acclaim by the Soviet press. The book was however followed by two other books, one on the Virgin Lands Campaign. Brezhnev's vanity made him the victim of many political jokes. Nikolai Podgorny warned him of this, but Brezhnev replied, "If they are poking fun at me, it means they like me". It is now believed by Western historians and political analysts that the books were written by some of his "court writers". The memoirs treated the little known and minor Battle ofNovorossiysk as the decisive military theatre of World War II.

Brezhnev's personality cult was growing outrageously at a time when his health was in decline. His physical condition was deteriorating; he had become addicted to sleeping pills and had begun drinking to excess and smoking heavily. Over the years he had become overweight. From 1973 until his death, Brezhnev's central nervous system underwent chronic deterioration and he had several minor strokes. When receiving the Order of Lenin, Brezhnev walked shakily and fumbled his words. Yevgeniy Chazov, the Chief of the Fourth Directorate of the Ministry of Health, had to keep doctors by Brezhnev's side at all times, and Brezhnev was brought back from near-death on several occasions. At this time, most senior officers of the CPSU wanted to keep Brezhnev alive, even if such men as Mikhail Suslov, Dmitriy Ustinov and Andrei Gromyko, among others, were growing increasingly frustrated with his policies. However, they did not want to risk a new period of domestic turmoil that might be caused by his death. At about this time First World commentators started guessing Brezhnev's heirs apparent. The most notable candidates were Suslov and Andrei Kirilenko, who were both older than Brezhnev, and Fyodor Kulakov and Konstantin Chernenko, who were younger; Kulakov died of natural causes in 1978.

Last years and death

Brezhnev's health worsened in the winter of 1981–82. In the meantime, the country was governed by Gromyko, Ustinov, Suslov and Yuri Andropov and crucial Politburo decisions were made in his absence. While the Politburo was pondering the question of who would succeed, all signs indicated that the ailing leader was dying. The choice of the successor would have been influenced by Suslov, but he died at the age of 79 in January 1982. Andropov took Suslov's seat in the Central Committee Secretariat; by May, it became obvious that Andropov would try to make a bid for the office of the General Secretary. He, with the help of fellow KGB associates, started circulating rumours that political corruption had become worse during Brezhnev's tenure as leader, in an attempt to create an environment hostile to Brezhnev in the Politburo. Andropov's actions showed that he was not afraid of Brezhnev's wrath.

Brezhnev rarely appeared in public during the spring, summer and the autumn of 1982. The Soviet government claimed that Brezhnev was not seriously ill, but he was surrounded by doctors. He suffered a severe stroke in May 1982, but refused to relinquish office. During mid autumn on 7 November 1982, despite his failing health, Brezhnev was present standing on Lenin's Mausoleum during the annual military parade and demonstration of workers commemorating the anniversary of the October Revolution. The event would also mark Brezhnev's final public appearance before his dying three days later after suffering a heart attack. He was honoured with a state funeral which was followed with a five-day period of nationwide mourning. He was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Red Square. National and international statesmen from around the globe attended his funeral. His wife and family attended; his daughter Galina Brezhneva outraged spectators by not showing up in sombre garb. Brezhnev on the other hand was dressed for burial in his Marshal's uniform, along with all his medals.

Legacy

Brezhnev presided over the Soviet Union for longer than any other person except Joseph Stalin. He is often criticised for the prolonged Era of Stagnation, in which fundamental economic problems were ignored and the Soviet political system was allowed to decline. During Mikhail Gorbachev's tenure as leader there was an increase in criticism of the Brezhnev years, such as claims that Brezhnev followed "a fierce neo-Stalinist line". The Gorbachevian discourse blamed Brezhnev for failing to modernise the country and to change with the times, although in a later statement Gorbachev made assurances that Brezhnev was not as bad as he was made out to be, saying, "Brezhnev was nothing like the cartoon figure that is made of him now".[104] The intervention in Afghanistan, which was one of the major decisions of his career, also significantly undermined both the international standing and the internal strength of the Soviet Union. In Brezhnev's defence, it can be said that the Soviet Union reached unprecedented and never-repeated levels of power, prestige, and internal calm under his rule.

Brezhnev has fared well in opinion polls when compared to his successors and predecessors in Russia. However, in the West he is most commonly remembered for starting the economic stagnation which triggered the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In an opinion poll by VTsIOM in 2007 the majority of Russians wanted to live during the Brezhnev's era rather than any other period of Soviet-Russian history during the 20th century.

Personality traits and family

Brezhnev's vanity became a problem during his reign. For instance, when Moscow City Party Secretary Nikolay Yegorychev refused to sing his praises, he was shunned, forced out of local politics and earned only an obscure ambassadorship. Brezhnev's main passion was driving foreign cars given to him by leaders of state from across the world. He usually drove these between his dacha and the Kremlin with flagrant disregard for public safety.

Brezhnev lived at 26 Kutuzovsky Prospekt, Moscow. During vacations, he lived in his Gosdacha in Zavidovo. He was married to Viktoria Petrovna(1908–1995). During her final four years she lived virtually alone, abandoned by everybody. She had suffered for a long time from diabetes and was nearly blind in her last years. He had a daughter, Galina, and a son, Yuri. Galina in her later life became an alcoholic who together with a circus director started a gold-bullion fraud gang in the later years of the Soviet Union.

Source: wikipedia.org, peoples.ru, news.lv

Places

| Images | Title | Relation type | From | To | Description | Languages | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | Bocharov Ruchey - is the summer residence of the President of Russia | resided | en, ru |

Relations

05.02.1901 | Feinkostladen Jelissejew (Moskau)

21.11.1935 | Первое присвоение звания Маршала Советского Союза

01.09.1939 | Invasion of Poland

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign or 1939 Defensive War (Polish: Kampania wrześniowa or Wojna obronna 1939 roku) in Poland and the Poland Campaign (German: Polenfeldzug) or Fall Weiß (Case White) in Germany, was an invasion of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the beginning of World War II in Europe. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week after the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, while the Soviet invasion commenced on 17 September following the Molotov-Tōgō agreement which terminated the Russian and Japanese hostilities (Nomonhan incident) in the east on 16 September. The campaign ended on 6 October with Germany and the Soviet Union dividing and annexing the whole of Poland.

28.09.1939 | German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation

The German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation (also known as the German–Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty) was a treaty signed by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union on September 28, 1939 after their joint invasion and occupation of Poland. It was signed by Joachim von Ribbentrop and Vyacheslav Molotov, the foreign ministers of Germany and the Soviet Union respectively. The treaty was a follow up to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, which the two countries had signed on August 23, prior to their invasion of Poland and the start of World War II in Europe. Only a small portion of the treaty was publicly announced.

30.11.1939 | Winter War

27.02.1942 | Publicēta Smoļenskas deklarācija

Atrodoties karagūstekņu nometnē Viņņicā, Andrejs Vlasovs - PSRS ģenerālis 2. Pasaules kara laikā piekrita sadarboties ar vācu varas iestādēm. 1942. gada 27.februārī Vlasovs izlaida t. s. Smoļenskas deklarāciju, kurā aicināja cīnīties pret PSRS.

22.03.1943 | Khatyn massacre

08.05.1945 | World War II: V-E Day, combat ends in Europe. German forces agree in Rheims, France, to an unconditional surrender.

01.11.1955 | Beginning of Vietnam War

14.02.1956 | XX съезд КПСС - осуждение культа личности Сталина

02.11.1956 | Ungārijas valdība paziņo par izstāšanos no Varšavas bloka un lūdz ANO aizsargāt no PSRS iebrukuma

29.03.1959 | Some Like It Hot

24.10.1960 | Nedelin catastrophe

The Nedelin catastrophe or Nedelin disaster was a launch pad accident that occurred on 24 October 1960 at Baikonur test range (of which Baikonur Cosmodrome is a part), during the development of the Soviet ICBM R-16. As a prototype of the missile was being prepared for a test flight, an explosion occurred when second stage engines ignited accidentally, killing many military and technical personnel working on the preparations. Despite the magnitude of the disaster, news of it was suppressed for many years and the Soviet government did not acknowledge the event until 1989. The disaster is named after Chief Marshal of Artillery Mitrofan Nedelin (Russian: Митрофан Иванович Неделин), who was killed in the explosion. As commanding officer of the Soviet Union's Strategic Rocket Forces, Nedelin was head of the R-16 development program.

17.10.1961 | The 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

14.10.1964 | Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was removed from power

29.03.1966 | Leonid Brezhnev became the First Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party of the USSR

03.04.1967 | Kinokomēdija "Kaukāza gūstekne"

05.01.1968 | Aleksandrs Dubčeks ievēlēts par ČSSR Komunistiskās partijas ģenerālsekretāru

05.01.1968 | The Prague Spring

20.08.1968 | The Prague Spring. Warsaw Pact countries invades Czechoslovakia

The Prague Spring (Czech: Pražské jaro, Slovak: Pražská jar) was a period of political liberalization in Czechoslovakia during the era of its domination by the Soviet Union after World War II. It began on 5 January 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček was elected First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), and continued until 21 August when the Soviet Union and other members of the Warsaw Pact invaded the country to halt the reforms.

26.09.1968 | "Pravda" publicē "Brežņeva doktrīnu", kas pamato sociālistisko valstu "ierobežoto suverenitāti" par labu krieviem (PSRS)

16.01.1969 | Protestējot pret Varšavas bloka valstu bruņotu iebrukumu Čehoslovākijā, pašsadedzinās Jans Palahs

Prāgas pavasaris bija liberalizācijas periods Čehoslovākijas Sociālistiskajā republikā, kas sākās 1968. gada 5. janvārī, kad Aleksandrs Dubčeks tika ievēlēts par Komunistiskās partijas vadītāju, un beidzās 1968. gada 20. augustā, kad PSRS vadītā Varšavas pakta bruņotie spēki iebruka valstī.

22.01.1969 | Brezhnev assassination attempt

02.03.1969 | Sino-Soviet border conflict

The Sino-Soviet border conflict (中苏边界冲突) was a seven-month undeclared military conflict between the Soviet Union and China at the height of the Sino-Soviet split in 1969. The most serious of these border clashes occurred in March 1969 in the vicinity of Zhenbao Island (珍宝岛) on the Ussuri River, also known as Damanskii Island (Остров Даманский) in Russia. Chinese historians most commonly refer to the conflict as the Zhenbao Island incident (珍宝岛自卫反击战) [4] The conflict was finally resolved with future border demarcations.

04.04.1970 | Netālu no Magdeburgas VDK virsnieki sadedzina Hitlera mirstīgās atliekas un pelnus izkaisa upē

11.12.1970 | 1970 Polish protests

The Polish 1970 protests (Polish: Grudzień 1970) occurred in northern Poland in December 1970. The protests were sparked by a sudden increase of prices of food and other everyday items. As a result of the riots, which were put down by the Polish People's Army and the Citizen's Militia, at least 42 people were killed and more than 1,000 wounded.

14.12.1970 | Grudzień 1970: robotnicy Stoczni Gdańskiej odmówili podjęcia pracy i wielotysięczny tłum przed południem udał się pod siedzibę Komitetu Wojewódzkiego PZPR w Gdańsku

Grudzień 1970, wydarzenia grudniowe, rewolta grudniowa, wypadki grudniowe, masakra na Wybrzeżu – protesty robotników w Polsce w dniach 14-22 grudnia 1970 roku (demonstracje, protesty, strajki, wiece, zamieszki) głównie w Gdyni, Gdańsku, Szczecinie i Elblągu, stłumione przez milicję i wojsko.

13.12.1971 | На экраны выходит криминальная комедия "Джентельмены удачи" - лидер кинопроката 1972 года

26.05.1972 | W Moskwie Richard Nixon i Leonid Breżniew podpisali układ o ograniczeniu systemów obrony przeciwrakietowej ABM (Traktat ABM)

Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty – traktat ABM podpisany w 1972 roku traktat między Stanami Zjednoczonymi a Związkiem Radzieckim o nieograniczonym czasowo ograniczeniu rozwoju, testowania i rozmieszczania systemów antybalistycznych (ABM – ‘’Antiballistic Missile’’). Jak wynika z art. I traktatu, jego celem było „ograniczenie systemów antybalistycznych każdej ze stron traktatu (ZSRR i USA) i zapobieżenie rozmieszczeniu przez którakolwiek ze stron systemów ABM na jego terytorium”. Jakkolwiek układ dopuszczał pewne ograniczone rozmieszczenie systemów antybalistycznych, jednakże zapobiegał utworzeniu systemów narodowych, w efekcie czego zapewniał nieskrępowaną możliwość balistycznego ataku jądrowego przez każdą ze stron. Traktat ograniczał możliwość rozmieszczenia systemów antybalistycznych jedynie do określonej w nim liczby rakietowych systemów lądowych oraz umieszczonych na Ziemi systemów radarowych.

07.01.1974 | Меховое дело в СССР

17.07.1975 | Apollo–Soyuz Test Project

01.08.1975 | Helsinki Final Act

26.12.1975 | Первый полет Ту-144, советского сверхзвукового пассажирского самолёта

10.02.1976 | Sejm przyjął, przy jednym głosie wstrzymującym się Stanisława Stommy, poprawki do konstytucji PRL. Wprowadzono zapis o przewodniej roli w państwie PZPR i jego sojuszu z ZSRR

14.04.1978 | Demonstrations against russification of Georgia in Tbilisi

17.09.1978 | Četru ģenerālsekretāru tikšanās

02.06.1979 | Pāvests Jānis Pāvils II ierodas ar vizīti Polijā. Tā ir pirmā pāvesta vizīte komunistiskās PSRS satelītvalstī

24.12.1979 | PSRS organizē valsts apvērsumu un ieved savu karaspēku Afganistānā

25.12.1979 | PSRS uzsāk karu ar Afganistānu

27.12.1979 | Operation Storm-333

19.07.1980 | Открытие Летних Олимпийских игр в Москве

26.12.1980 | Убийство на «Ждановской»

13.12.1981 | Vojcehs Jaruzeļskis Polijā pasludina karastāvokli

Kara stāvoklis Polijā (Stan wojenny w Polsce 1981-1983) ilga no 1981. gada 13. decembra līdz 1983. gada 22. jūlijam

13.12.1981 | Martial law in Poland

Martial law in Poland (Polish: Stan wojenny w Polsce) refers to the period of time from December 13, 1981 to July 22, 1983, when the authoritarian communist government of the People's Republic of Poland drastically restricted normal life by introducing martial law in an attempt to crush political opposition. Thousands of opposition activists were jailed without charge and as many as 100 killed. Although martial law was lifted in 1983, many of the political prisoners were not released until a general amnesty in 1986.

11.02.1982 | Начало дела о Кремлевской коррупции

28.06.1982 | Сочинско-краснодарское или «Медуновское дело»

02.07.1982 | Ilgais ceļš kāpās

15.11.1982 | Ilggadīgā PSRS Kompartijas vadītāja L. Brežņeva bēres

11.03.1985 | Mikhail Gorbachev was appointed General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party; leader of the Soviet Union.

18.10.1989 | Erich Honecker resigns as General Secretary of the East German Socialist Unity Party of Germany

26.12.1991 | PSRS oficiāli beidz pastāvēt

01.02.2011 | Десталинизации россиского общества Караганова

14.11.2021 | Aivars Borovkovs: Runājiet ar vecākiem un vecvecākiem, kamēr viņi vēl dzīvi

“Izmantojiet laiku. Kamēr vēl iespējams – parunājiet ar saviem vecākiem un vecvecākiem. Uzziniet par notikumiem, piemēram, “Hruščova atkušni”, Atmodas laiku. Ja atrodat kādus fotoattēlus – saglabājiet tos. Jo cilvēki un lietas aiziet, pazūd. Daudziem mājās ir atmiņu krājumi, kas nevienam nav vajadzīgi. Un tomēr... tie ir vajadzīgi. Tā ir tautas atmiņa, kas jāuzkrāj,” aicina Aivars Borovkovs, jurists, fotogrāfs, dzīvnieku tiesību aizstāvis un – kopā ar kolēģi Ainaru Brūveli – pasaules kultūrvēsturiskās enciklopēdijas “timenote.info” veidotājs. Tumšajā veļu laikā – domāsim kopā.